I've always resisted the notion that things disappear. In metaphysical terms, this stubbornness manifests itself in my credulity about the existence of ghosts, angels, demons, and other paranormal residues of entities that linger just outside our ability to perceive them. Similarly, there is a part of me that responds to D's or my habitual loss of keys or important documents with the bald pragmatism of the law of conservation of matter: "Well, they can't have disappeared into the ether. They have to exist right now somewhere." In the end, I guess I just have a naïve faith in the intrinsic findability of things (though I would add that my life would be much easier if it came with a Command+F function).

For over a month, I've had an open Word document that I keep minimized on my computer's desktop. It's the beginning to a poem that I'm not sure yet how to finish. Here's what it says:

|

| D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths (1962) |

It's an interesting story, but I still wonder, why did this one in particular capture my imagination so powerfully? Because it expresses the view that only a part of life happens above ground in the quotidian world of daylight, and the other part transpires in some hidden underworld of cold darkness? Because Persephone finds love in the latter realm, and not in the sunshine of her springtime-goddess mother's world?

(And by the way: how does Hades get his newfound love to stay in the underworld with him for a handful of months of every year? By tempting her to eat something, of course.)

|

| Source: Richard Gary Garvin, "Erasing History" (from Fictions) |

The irresisitable proliferation of graphomania among politicians, taxi drivers, childbearers, lovers, murderers, thieves, prostitutes, officials, doctors, and patients shows me that everyone without exception bears a potential writer within him, so that the entire human species has good reason to go down the streets and shout: 'We are all writers!'There is, of course, more than a little self-deprecation here—after all, he is himself a novelist who has written reams of prose. Indeed, the irony isn't lost on me, either: I bring up this idea on a blog whose entries get lengthier and lengthier with each new post. And few of us are exempt: think of how our Facebook status updates tend to accumulate.

We write, at least in part, to be remembered. Kundera's novel was the first time I ran up against this idea in literature, but it was certainly not the first time I feared I would disappear.

One of the things I love about the internet is that you can start with the most obscure reference possible—for instance, Nathaniel the Grublet, a 1970s Christian album-and-comic combo narrated by Dean Jones—and find images and sound files for it doing a simple Google search. I was given the comic and album as a kid, and I listened to it once and could never get through it again. It scared me badly enough that I would think of it sometimes at bedtime and be unable to fall asleep. Recently, I discovered a site where someone had posted the entire thing, and on YouTube I found I the song that had once frightened me, so I sat and listened to the track again. It isn't scary. Well, most of it isn't—now. This part, and the song that went with it, scared the bejeezus out of me at the time. Yes, I know how ridiculous that baritone sounds. (Is it altered? I kind of hope so, because I wouldn't want to think there's someone running around who actually has a voice like that). The creepy laughter is especially hilarious now. But back then? Terrifying. And the text was even more disturbing: if you strayed too far into Direwood, then like Persephone, you would disappear. But disappear not just into a hole in the ground, or into a relationship with the lord of the underworld. You would dissolve completely into nothing.

|

| I don't know, man. I was scared of weird things when I was a kid. Well, I mean, I'm still scared of zombies and evil clowns who live in storm drains. Source: here. |

Another example: one day when I was somewhere between eight and ten years old, I was sitting on the crumbling edge of the asphalt driveway at our house in Cedar Crest subdivision, and unprompted by anything, I thought to myself, What if I don't exist? This sounds really trite, so let me add that it wasn't as much a conscious sentence that popped up like a subtitle in my head as it was a sudden, overwhelming conviction that the world had bottomed out. My vision darkened and tunneled for a few seconds, and I felt blind panic. I still don't know where the feeling came from.

Lately I keep having a similarly terrifying, involuntary spell of panic that lasts a couple of seconds: the life I think I am living is a blink-of-the-eye dream I'm having in some other, "actual" life, in which I have momentarily dozed off while driving and will shortly wake to find I'm careening towards a tree at full speed, unable to stop in time.

Just over three months ago, I watched my Nana die. She's the first person I've ever seen at the moment she disappeared.

I had said at a couple of points during the preceding week that being there with Nana had been like sitting with someone who was waiting for a bus. It was far more tedious than I had expected. It required patience, both for the waiter and those who waited with her. The moment of death was was not what I thought it would be, either. I wasn't present when Rhea died, and that has always bothered me, for multiple reasons. I wanted to stay near her so that she wouldn't feel alone. But some of my regret was plainly selfish: I suspected that I had missed out on a mystery that others had gotten to witness. When I asked Jeff and Mom about Rhea's last moment, they weren't really able to describe it to me in a way I could understand or picture. So I thought that if I could be there with Nana, then I could both keep her company and also come to understand something more about death. I also felt, in some ridiculously Capricornian way, that not to be present for the moment itself would negate all the sitting and waiting I had done for the ten days up to that point. It would mean I hadn't "done a good job." At any rate, I had expected the moment of death to be dramatic, a definitive ending, accompanied by a flourish, a puff of smoke, a gasp of air, or a chariot of fire. Poof. Instead, it was more like watching someone walking into the distance until she was only a speck, and then she finally disappeared entirely, but you could never say exactly at what precise second it had happened. Even afterwards, your eyes might trick you into seeing phantom, residual movement.

Here's how it went. That afternoon, my mom called when I was at the grocery store. I had felt stir crazy and needed to get out of the house for a while, so I volunteered to go and get some ingredients for dinner. Luckily, I had only gotten as far as the olive bar, where I'd already dipped out some miniature mozzarella balls and pitted kalamatas, when my phone started buzzing in my straw purse. I picked up, and with no preamble my mother said with quiet intensity, "She's in the process." Just as she said it, I could hear her turning away from the phone and cooing, "You're doing just fine. You just stay or go whenever you're ready, sweetie." I sprinted out of the store and left the half-filled container sitting on the ledge of the bar, right by the giardiniera bin.

When I dashed into her bedroom five minutes later, Nana was almost gone. Her breaths had spaced out so much that it was hard to discern them. I had time to say a couple of sentences, something like, "I think you're very brave. I admire that you found the courage to be happy and to live your life your own way. I love you." And then she took one, maybe two more breaths over the course of a minute or so. That was all. Reading that sentence, it strikes me as deceptively definitive. It wasn't like that at all. In fact, we all sat very still for several minutes, not talking. Finally, someone said, "...Did it happen? Is she gone?"

I believe those last moments are important, even if our fate is oblivion. Which I don't think it is. But I can't prove that.

The night after I got home from Tennessee, I finally sat down to watch Melancholia, which I had been meaning to do for a couple of weeks. I knew it was going to be heavy, but I figured I was in mourning already, so what better time to launch myself into a movie whose very title is a synonym for depression? I'm still mulling it over (sometimes it takes me months to really decide what I think of a movie), but my overall responses are as follows: it was compelling. And scary. And beautiful. And full of pathos.

I feel obligated to say SPOILER ALERT here, though there's really no point, as the film gives away the ending in its opening sequence. This is a suspenseful film, but not because you don't already know what's going to happen.

The premise of the movie is that the world is about to end. There is a planet that has been hiding behind the sun, and it is headed for earth. Scientists have said that it will likely merely pass by us, but margin of error being what it is, that outcome isn't certain. The subsequent reactions of the different characters—particularly the sisters Claire and Justine—are what makes the movie interesting. What's also terrifyingly stunning is the final sequence of the movie, which I'll link to here, in case you've either already seen the movie or aren't planning on it.

The movie offers the ultimate termination. Everything disappears into a ball of fire, along with anyone who might be left to tell about it. A cold, empty universe, entirely bereft of life. There is a seductive, paralyzing finality to Von Trier's vision, and watching it felt like being hypnotized by the eyes of a snake. THE END. I couldn't look away from those last few seconds. After the credits rolled, I went searching for YouTube clips of the scene so that I could watch it again another half dozen times.

It made me think of the hardest poem I ever wrote about as a student: Philip Larkin's "Aubade." I've still never come to terms with what it says.

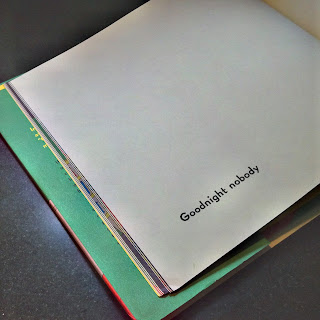

That kind of disappearing leaves me stunned and white with fear. It's not the fear of hell after we die. It's worse: the fear of nothing after. When I think of it, I feel like Esme, who responds to a trip to the vet by going as still and cold as possible, almost as if this will keep her safe—or, to put it more earthily, as my mom used to say about our cat Louie at her vet check-ups: "If she could have curled herself up and put her head up her own ass and disappeared, she would have." The idea of nothingness is exactly what strikes me, now as an adult, as the more sinister echo in one of my favorite childhood books, Goodnight Moon.

After the nothingness in these last goodnights, I was always reassured by the final page, in which we're back in the darkened room again with the dying fire and the dim yellow lights in the dollhouse windows, the comb and the brush and the bowl full of mush, and, presumably in the next room, the quiet old lady, whispering hush.

In the face of the twin possibilities of vanishing and nothingness, illusions can be comforting. A bit of sleight of hand, and things feel manageable again—even if it's only the symbolic protection of the "magical" tipi skeleton at the end of Melancholia.

When we were little, my siblings and I created an entire imaginary town called Greenwood, as well as pseudonyms for ourselves (Jeff was Johnny, Rhea was Linda, and I was Rosie). We also invented an invisible, evil nemesis named Kevin. We fought this individual we couldn't see, and even though he occasionally dinged us or won minor victories, we always triumphed over his nonentity.

It's a silly example, yes, but I don't think we ever completely leave this tendency to illusionism in childhood. A little over ten years ago I wrote D a letter in which I talked about my experiences in counseling. I had been seeing Cindy for a couple of months at that point.

I'm wondering what "crazy" even is, to begin with. Last week, I was telling Cindy that I notice I'm continually evaluating the way I grieve, trying to assess whether I'm doing it the healthy (translation: the right) way. She almost laughs—in an affectionate and only mildly derisive way, of course—at how I'm always so concerned with "doing the right thing." Then she told me the story of meeting another therapist at some conference. This woman confided to Cindy that her son had died; but then she said she's always telling herself that he's in the Witness Protection Program, and that's how she deals with his absence. I expected Cindy to say that the woman is in denial, but she didn't. And when I think about it, obviously this woman knows that her son is dead, or she wouldn't be able to say it at all. The illusion of the Witness Protection Program is just something that helps her to get through, and as long as it isn't getting in the way, what harm does it do? Okay, I'll concede that it is extraordinarily odd; but I'm wondering if it's necessarily a bad way of dealing with things.And I took that a step further:

Then I started to consider other "useful fictions" that we have, which we never even think about, but which make it possible for us to live and function daily in our world. For instance, the borders of countries aren't real; it's not as though there's a dotted line imprinted across the bottom of Canada that you can actually see on the ground, like you can in cartoons or on maps. Political borders are largely made up and arbitrary, and they only work because we all agree to pretend that they're actually there. The only reason they seem real is that, in practice, we act as though they are. Money is the same way. It's a piece of cloth or paper that technically has no inherent value, but we all agree to pretend that it's backed by a certain amount in gold. The reason it works is that we all (or most of us) participate in the illusion. Moreover, now that there's no real gold standard anymore to back it up, it's even more of a fiction. You can't drive over to Fort Knox and trade in a stack of bills for the same amount in gold bullion.

And we don't consider our belief in either of these things—the borders of countries or the value of money—to be delusional. They are useful fictions. They help us live. So why should we criticize people for dealing with loss similarly, by creating useful fictions for themselves?

Larkin might—although he doesn't really have a leg to stand on. He worked too much and got drunk to get away from it, himself.

A couple of years ago, D and I went to see David Copperfield perform in Las Vegas. D was having some doubts about his vocation at the time. We all have those moments: is this really my true career, my calling? Am I actually meant to be a teacher / doctor / bookkeeper / contractor? Am I digging myself further and further into a hole of my own making? And if so, will the person I know as me eventually disappear? D wanted to tell the magician how important his work had been to him, especially back in high school and college, when D himself had a side job doing magic at birthday parties. I don't know what his impression of the great illusionist was, but I can tell you mine: David Copperfield looked tired. Existentially tired. The man has to be as wealthy as Midas, with plenty of money to buy any kind of leisure he likes, so I could only guess at what had worn him out. Two shows a day in Vegas? Family or woman troubles? Something as simple as a late previous night? Or is it something more global—say, a life devoted to illusion? He is, after all, the Guinness Book world record holder for the largest disappearance ever performed by a magician.

So, while I acknowledge that we've all resorted to illusions to help us manage our anxieties, I'd like to think that it doesn't have to require hocus pocus. In the end, I want to subscribe less to Larkin's fear of disappearing and aspire more to Mary Oliver's ability to embrace the liberation and beauty of nothingness, of dissolving completely into the sea and air and earth.

This afternoon I sent a request on LinkedIn to reconnect with an old friend of mine from my grad school days at Tennessee, someone with whom I used to get roaring drunk on wine and rant for hours on end about books and religion and men. I wrote to her, "Hi, Anita—it's so good to see your name after all these years! How have you been?" Then I thought I'd see if I could find her on Facebook, but the only hit that came up when I searched for her full name was a memorial page. Imagine my shock when I clicked on it and learned that the page was for my friend, and that Anita disappeared suddenly from this earth over a year ago.

All day today I have sat and worked on the sofa in the keeping room, in front of windows perched at the height of the canopies of a pair of gigantic oaks. It's like being in a treehouse. When I look out, I see fluttering green-sheened leaves on long branches. This morning, as I stared at the essays appearing on my computer screen and then disappearing as soon as I'd bubbled in my score, I watched the sun's progress across the kitchen: muted sunlight splotching the cabinets, and then the chairs, and then Esme's fur as she slept on the ottoman, mottling the floor in dappled patterns as it migrated back towards the window. Then the sun swung overhead, disappeared from the inside of the house, and made the day outside so bright that it was hard to see my laptop's screen. Late this afternoon, I went to open some windows to let in the breeze of this first day of real fall weather, and with the sun behind me now, I was almost blinded by how absurdly deep the sky's color had gotten. It was so blue that the lower part of the yard looked like the bottom of an aquarium, its half-submerged rocks almost purple with reflected skylight. Involuntarily, the thought came: This has been the most beautiful day of the year. Go on, hurry up and go for your afternoon run. The light is leaving. Today is vanishing.

Sometimes it happens even faster. Recently, between appointments with students, I noticed that the entire concrete wall outside my basement office's window (my air shaft view, which I don't complain about; my last office had no window at all) was suffused with blazing sunshine. I watched, marveling, as the light ran its fingers rapidly over the textured cement and scaled the entire ten-foot wall in as many minutes.

My insight here is not new. Writers old and young, adept and hack, have worn this idea until it's about to disintegrate. So I'll just offer one last bit of an anecdote.

During the years when I knew Anita and took the poetry workshop in which I wrote all those little polished gold nugget poems, our professor invited the poet Brenda Hillman, who was in town for a reading, to come and speak to our class. That afternoon, we arranged ourselves into a circle of chairs, and she chatted with us about form, subject, point of view, experimentation. She was elegant, athletic, passionate about her craft. It was wonderful. But the thing that has stuck with me for the twelve years since that class was one comment she made about what happens after death. In the midst of a discussion about her book Death Tractates—which, after the sudden passing of her friend and mentor, she stopped work on another book to write—she said of her friend: "It wasn't that I felt she was gone. It was just that she was inaccessible now."

Someday soon I'll tell you my own ghost story, which makes me suspect Brenda Hillman is right, that people don't vanish forever. For now, go bake this custard. You won't have any trouble making it disappear—trust me.

buttermilk custard

1/2 c. (or one stick) unsalted butter, melted

1 c. sugar

3 large eggs

1 tsp. vanilla extract

1/4 c. flour

pinch of fine-grain sea salt

1 c. buttermilk

Preheat oven to 400 degrees and grease a glass pie dish or a tart pan with butter. (Or use the pie crust you've already parbaked.)

Sift together flour and salt into a small bowl.

In another, larger bowl, beat together butter and sugar for a couple of minutes with a whisk.

Beat in eggs, one by one. Beat in vanilla.

In three batches, whisk in buttermilk and dry ingredients, alternating them.

Pour into greased dish. Bake for 10 minutes at 400 degrees.

After 10 minutes, lower heat to 350 degrees and bake for an additional 50 to 60 minutes, until center is set (i.e. jiggly but not liquidy). If at any point it starts to brown too much, loosely cover the top with some foil.

This dessert will set best if you cover it, put it in the fridge, and let it rest for a few hours before you serve it.

4 comments:

This hit home (as usual) in a number of ways, not the least of which being that it seems we will soon be on a journey to be with one of our parents in the way you so beautifully describe being with your grandmother.

I'm also prepping to teach an overview of the sublime tomorrow, and Burke seems to sum up some of what you were getting at here (though I choose your blog any day): "Infinity has a tendency to fill the mind with that sort of delightful horror, which is the most genuine effect, and truest test of the sublime."

And, indeed, your blog IS sublime. (ba-dum-ching!)

Love,

S

Thank you for your kind comments, my dear friend. I wish I knew more about Burke -- I just know the thumbnail version -- but I love it that you mentioned his notion of the sublime. That's exactly the feeling Melancholia gave me.

It's funny; I've ended up learning a lot this year from my parents, both about them, and about what I have to look forward to and prepare for in the next few years...

I've never witnessed anyone pass away before, but I have imagined it to be very violent - like having something taken away that is meant to be kept.

I'm so sorry for the loss of your grandmother. I've lost all four of my grandparents and I miss them a lot. I wish I could sit on a porch with them and pick their brains about the secrets of the universe. I wish they could know the person I am today and I wish they told more stories.

I really liked this post Heather - very warmly written.

Cheers,

Tanvi

Thank you, sweet Tanvi! It makes me sad, how long it has taken me to truly appreciate my grandparents. I'm sure it will only deepen as I get older. Thinking about all this also redoubles my desire to have as many conversations with my parents as possible, and not to take those for granted.

I'm really enjoying your photo blog, by the way. You take gorgeous pictures.

Post a Comment