Years ago, I took the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and tested off-the-charts INFJ: introverted-intuitive-feeling-judging. It always felt like an apt description of me, both the good and the bad of the type. Some people think the MBTI, a personality indicator with sixteen possible types, is the equivalent of silly horoscopes or tarot readings, just a fun little parlor game, because it's based on a self-reported questionnaire and not a "scientifically objective" measure of personality. Still, I've found it useful over the years. Because it is non-judgmental - it describes a neutral set of preferences - it has helped me to better understand, anticipate, and accept what motivates others and even myself, and how we view and navigate the world differently. According to the seminal text Please Understand Me II, the sixteen personality types are evenly classified into four temperament groups, each of which has a completely different aspiration. SJs want to be Donald Trump. SPs want to be Jimi Hendrix. NTs want to be Albus Dumbledore.

According to this book, like the three other "Idealist" NF types, an INFJ like me aspires to be Confucius:

The Sage is the most revered role model for the Idealists—that man or woman who strives to overcome worldly, temporal concerns, and who aspires to the philosophic view of life. Plato, perhaps the greatest of all Idealist philosophers, characterized the sage by saying that the "true lover of wisdom" is on a metaphysical journey [...] To transcend the material world (and thus gain insight into the essence of things), to transcend the senses (and thus gain knowledge of the soul), to transcend the ego (and thus feel united with all creation), to transcend even time (and thus feel the force of past lives and prophecies): these are the lofty goals of the sage, and in their heart of hearts all Idealists honor this quest. (145)But what's funny about this description of the sage is how loftily abstract it is, with its language of rising above the earthly world to a place of transcendence—especially when you look up the word in the OED and read how pragmatically the grandaddy of dictionaries defines the quality of being sage: "Practically wise, rendered prudent or judicious by experience." And also: "Characterized by profound wisdom; based on sound judgment." According to the OED, any transcendence the sage has achieved comes, paradoxically, directly from having kept both feet on the ground, having lived through an experience, and having returned with practical wisdom to dispense humbly to those who solicit it. Sages are sage because they've been there.

|

| I love sage. Sagey, sage, sage. |

I've been devouring memoirs like this for the past year, as I told my analyst recently ("my analyst": I sound like either Woody Allen or a 1950s ad man), and the best way I can explain why I read them is this: because I want to know how these people did it. I should specify that "it" includes anything difficult. "Did it" could mean wrestled with grief, created a new career from scratch, engaged in successful self-promotion, braved a wilderness, distinguished oneself healthily from one's loved ones, taught for several decades and kept it fresh, survived a miscarriage, survived a betrayal, rose up through the ranks of the New York restaurant scene, sought and found beauty every day, or stayed politically engaged without either having one's heart crushed or becoming cynical.

How did they do it? I want to know. Not so I can do it the same way, but so I can use their way as a prototype while I figure out what my way will look like. This is how I approach recipes: if I want to make something, I do a Google (or better, an Epicurious) search, find a handful of promising ones, read them carefully, noting proportions and similarities, and then synthesize them into a general template for how to make the recipe my own. I did it with the tarte tatin, the vichyssoise, and the sangria.

And the sausage gravy, subject of this post. I learned the basic template of how to make it from my mom. She learned how to make it from her mother.

|

| New Year's Eve |

Until recently. Last month, she underwent a round of chemo and radiation to treat her non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and now that that's in remission, she's run aground on some serious heart troubles. My mom called me yesterday crying because she's worried about her mother, who is tired and can't get her breath. I'm worried about her, too, and I thought to myself today: I should write about this soon. Not now, but later, when we're safely past the scary part and I can calmly describe how frightened we were at this point.

I think of a poem by the wry and wise Emily Dickinson, which I found a few weeks ago in a used book that I bought while I was in Knoxville:

In so many chilling words, Emily tells us: "What you think you see is not the shore. I used to think it was, too. There are more rough seas, and they get worse. Trust me; I've seen." (This also makes me think of the line D likes to quote from Young Frankenstein: "Could be worse: Could be raining." At which point it begins to pour.) So here I am, I admit it, fretting about Nana's health. I don't know how this will turn out. My mom says Nan has used up about five of her nine lives. But heck, the lady keeps coming back from the verge of death to tell about it.

Jack Gilbert: another sage. He explains his grief for his wife as authentically as Tennyson does for his friend A.H.H. in his monumental work In Memoriam, yet in even fewer, simpler words:

|

Or read it here.

This poem says: "Grief takes forever. Please don't think that you'll ever overcome it—the best you're going to be able to do is manage." But even he doesn't have all the answers: later in The Great Fires, the same collection of poems, he admits that shortly after Michiko dies, "other Japanese women" enter the house and he no longer knows whether the black hairs he finds in the carpet are hers or someone else's. My mom has said she read somewhere, "Women mourn. Men replace." I don't know if that's true, but I can't entirely blame Jack for moving on to the next thing. (Can I call him Jack? I'm going to, just for meanness, just because he seems like a monolith carved from stone.) I do admire his monumental wisdom about grief. But he's only human.

I mean, pedestals are dangerous contraptions. Robert Bly warns about the danger of putting all our faith in wise men in A Little Book on the Human Shadow: "Many American women and men in the last century have projected their spiritual guide onto an Asian guru; that projection lasts a while, and then starts to rattle. Perhaps a student hears that his or her guru is sleeping with young girls, or buying Rolls-Royces by the dozen" (32). At some point, Bly argues, we have to realize that our spiritual guide can't be put out there onto someone else, onto someone who must inevitably fail us because of his or her own hypocrisies or inconsistencies. Ultimately, our guiding spirit has to come from inside us—whether we call that guide a conscience, a center, the Holy Spirit, Tao, or the soul. It's why I went into analysis. The first thing my analyst said was, "Your soul has gone to sit outside someone else's tent. You need a shaman to help you bring it back." I loved that.

I would argue that it sometimes helps to listen to the stories of people who have been there. Moreover, if we're now there ourselves, it certainly doesn't hurt to have the solidarity of some shared experience; it makes us feel like we have a bit of company before we have to set off again alone, guiding ourselves slowly towards some long-distant harbor. It also helps to know that even the brave ones among us didn't always know exactly where they were going.

|

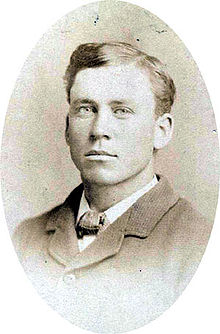

| Almanzo Wilder (photo credit) |

In this largely historically accurate novel, Laura and her family move from their homestead to the town of De Smet, South Dakota, for the duration of what turns out to be an extreme winter. Near the end of the book, during the height of the worst blizzards, the townspeople have begun to starve after an abnormally long period without any trains or supplies. Laura's future husband Almanzo Wilder and his friend Cap Garland agree to ride twenty miles over the suddenly foreign landscape of a prairie transformed by snow, in order to bring back a store of wheat that, it is rumored, is being hoarded by a bachelor wintering out on an isolated homestead. The pair know that there will likely only be a day's respite before the next zero-visibility blizzard sweeps across the prairie, so they have to work quickly. On their quest, they don't even know which direction they should be headed or where the man they're looking for lives. There are no signposts; everything is covered by a terrifyingly mute blanket of whiteness. The men lose their way several times. They finally find the homestead, lunch with the man, talk him with difficulty out of some of his wheat, and head back. The return trip is even slower going: they discover to their chagrin that the bottom layer of snowfall on top of the slough grasses has made a hollow crust, which their wheat-laden, horse-drawn sled periodically falls through and must be extricated from. At the halfway point, they look back at the northwestern horizon, where they see a gathering haze massing itself unmistakably into yet another fast-approaching storm cloud that will obliterate the stars overhead, one by one, and almost certainly overtake them before they reach the town. De Smet stands alone, surrounded by nothing for dozens of miles in every direction, and if they don't pull into town by the time the whiteout hits, there will be no buildings along which to feel their way home, and they'll wander out and freeze to death on the open prairie.

I won't tell you what happens because you should really read it. Laura married Almanzo, anyway, so the answer should be obvious. He was gutsy. He ventured out there because he had to, and he returned to tell about it.

Most days, my students look at me like I know what I'm talking about, like I've been there. Sometimes, when I'm being honest, this strikes me as funny. At those moments, I take great pleasure in assigning Anne Lamott's wonderful essay, "Shitty First Drafts," hoping she'll disabuse them of the belief that as soon as any "good" writer sits down to a computer, the perfect first draft should cascade over her like a rainbow waterfall of divine afflatus. I tell them that I once wrote a 200-plus-page book while convinced the majority of the time that I had no idea what I was doing. That I literally cut it into pieces with scissors and Scotch taped it back together in a different order to see if it would make any more sense that way. That if someone doesn't stop me, I will overuse the hell out of the word "however," beginning every other sentence with it so that, rhetorically, I'm like a dog turning in circles and never lying down: constantly making a statement and then reversing it in the next thought. That every time I sit down to write a paper or email or job letter or post—including this one—I feel panic when I confront the blank whiteness of a new Word document. And for the students who are really serious about their writing, I think it helps to hear this from someone who's been at it a little longer - not that experience makes all that much difference.

So, in the end, I guess my own definition of a sage would be different from what's in the dictionary. It would be something like: A person who comes back with news and supplies.

And speaking of supplies, here is the promised recipe. It's based on a really easy two-part equation: 1.) fat + flour = roux. 2.) Whisk in liquid. Voilà: gravy. There are all kinds of gravy—I'm a huge fan of brown gravy and red eye gravy, too - but this kind is creamy, very sagey and sausagey, and delightful.

I'm sure D would have me add, as well, that you should have soul music playing in the background and it should be a Saturday morning when you make this. There should also be a cat lying in a patch of sunlight on the floor. Those are equally crucial ingredients.

Recipe note: I know this seems like a wildly contradictory list of ingredients—e.g. pork fat and skim milk—but you are welcome to substitute the real thing, dairy-wise. I just use nonfat milk because the fat content is so high for the pork products and butter, and this makes the gravy slightly less profanely horrible for you.

sage sausage gravy

1 tsp. rubbed sage (i.e. dried)

half a roll of sage breakfast sausage

2 tbsp. bacon drippings (from about 6 slices of bacon)

1 tbsp. unsalted butter

2 to 3 tbsp. all-purpose flour

1 to 2 cups skim milk

1 cup fat-free half-and-half (Land-O-Lakes is good)

Preheat oven to 375 degrees.

If you already save your drippings, you won't have to be making any bacon (heh-heh). If you don't have any reserved drippings, then you'll need to fry up a skillet full of bacon slices. When they're nearly done, incline the pan slightly so that the drippings run down and the slices drain well, and then remove the bacon and save it for your breakfast tomorrow. Remove drippings to a small bowl, but don't wash the skillet.

Turn up heat to medium and crumble sausage into the pan with your fingers. Wash your hands. Add 1/2 teaspoon of the rubbed sage. Fry sage and sausage until the latter is browned and just cooked through. Drain it as well as you can, again by inclining the pan, and then carefully remove sausage to a plate.

Reduce heat to low. Add bacon drippings and butter to pan with sausage drippings. Try to get enough fat to equal about 3 or 4 tablespoons total; this means you can adjust, with more or less of the butter and bacon and sausage drippings, depending on what you have. Add the other 1/2 teaspoon of sage and let it fry a little infuse the fat with its flavor.

And now for the roux. Add about two heaping tablespoons of flour and stir it around until it's all incorporated into the fat. If it's still pretty liquidy, add a bit more flour. You want it to turn into the consistency of paste. Let it fry for a minute or two, until it gets golden and loses its raw floury taste.

Turn heat up to medium-high and add a cup of the milk, whisking to incorporate it with the roux. You will likely need to be ready to add another cup or so of the milk in pretty short order, as the gravy thickens quickly. Add the half-and-half. Let the gravy boil for a few minutes, until it starts to really thicken. At this point, you can add a little more milk and/or half-and-half, to make it the consistency you like. (D likes his gravy very, very thick. I like it a little thinner.) Add salt and lots of pepper to taste.

Add the sausage back into the gravy, and lower the heat to low. Let the gravy simmer for about 10 minutes or so, so that the sausage can re-infuse the gravy with sausagey-ness.

At some point during all this craziness, decide about your bread. If you're a biscuit person, put about six frozen biscuits (I recommend Pillsbury's Southern Style biscuits) into the oven on a greased or parchment-lined baking sheet. Let them bake just until their tops are getting golden, about twenty-something minutes. I have a thing for slightly underdone biscuits, and so does D, but if you want yours more done, let them go for a little longer.

If you're like me, though, you might like the gravy on toast. I'm a fan because my mom often wouldn't have the time or the can in the refrigerator to make biscuits, so she'd just make some dry toast. Because the gravy is so rich, I actually like it on torn-up dry toast better than I do on biscuits. Your call.

Plan for a nap after this one. Trust me; I've been there.

- H.

No comments:

Post a Comment