Today many in the Western Hemisphere are celebrating the Day of the Dead, All Souls' Day, or both. It is a day when they remember dead friends and relatives by visiting their graves and leaving food for them. For Catholics in particular, it is a day to pray for the souls of those believers who died un-sanctified of their venial sins and thus linger in purgatory, waiting for the intercessory appeals of their loved ones to help them gain entrance into heaven's visio beatifica.

Speaking of lingering spirits, I have a confession to make: if the show Ghost Whisperer is on TV, I will watch it. (The same is true of Sleeping with the Enemy, but that's a subject for a different post.) While I'm always interested to see Jennifer Love Hewitt's latest lingerie-inspired outfit or fairytale hair extensions, I know that's not the whole reason why it's so mesmerizing. When I confessed my weakness for the show to D, he laughed at me. Until one day when it came on while we were hanging out. He watched the hokey opening credits and said disdainfully, "I don't get it. What's the appeal?" I replied, "You just wait. This show is a black hole. By dinnertime you will have watched several episodes and you'll wonder where the afternoon went." Three hours later I asked him, "So? It's compelling, right?" D just shook his head slowly and said, "How did that happen?"

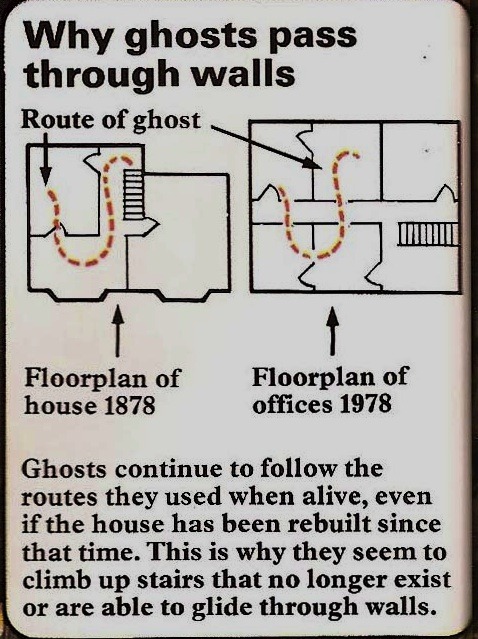

|

| Source: Long-Forgotten |

Last night, I got into bed and pulled out The Best American Poetry 2012, which D bought for me at a bookstore in San Francisco a few weeks ago. (When I walked out that afternoon smiling and hugging the book to my chest, he said, "Do you know how much I love you?" For my part, I feel lucky to love a man who appreciates the poetry and mystery of life and death.) I did the "plop method" and happened to choose a poem by Reginald Dwayne Betts, called "At the End of Life, a Secret." In it, Betts alludes to the work of Dr. Duncan McDougall, an early 20th-century physician who postulated that the soul was material. McDougall created an apparatus capable of weighing the bodies of terminally ill patients, both as they approached death and immediately afterward. Based on his subjects' average loss of mass at the moment of death, he concluded that the human soul weighs around 21 grams. This is where we get the famous cultural belief about the mass of the soul, and also where the 2003 film of the same name got its title. Betts's poem is critical of McDougall's attempts to measure the mass of the soul, and Betts points out that while we can weigh the different organs of the body after death, there are many things we cannot quantify, measure, or describe: "there is no mark to suggest you were / an expert mathematician, that you were / the first runner-up in debate championships, / 1956, Tapioca, Illinois." To be sure, MacDougall's experiments have been received with mixed responses. Most believe that his sample size was too small and his methods imprecise (for more on that, see this Snopes article). A few acknowledge his experiments as an initial scientific contribution to the debate surrounding the soul's existence and composition. Still others believe the soul must be made of energy, not matter. Yesterday when I mentioned this to Valerie, she said, "Maybe the soul is both matter and energy," and then mentioned string theory. But whatever that spiritual engine is that animates us, propels us, guides us through life—there is a wealth of anecdotal evidence that suggests there might be a remainder that escapes at the moment of death (whence and to where?), something that occasionally lingers in places on this earth.

I had a friend named Annette whose tales of spiritual residues were so vivid that they made me suspend disbelief. I met her through another friend, a man who was, appropriately, perhaps the most skeptical, pragmatic person I've ever met. Over dinner one night, pointedly ignoring his incredulous smile across the table, Annette told D and me about a spirit who lingered for a long time in the house where she lived alone: he used to get in her face and try to intimidate her, and once he even pressed down on her while she was in bed. "Finally," she said matter-of-factly, "I just told him he had to leave. I never sensed his presence again." Annette was less breezy, and much more moved and troubled by another presence that haunted her over the years: her father's ghost, who used to drop dimes all over the house. Often, she said, she would turn and see a coin fall from chest height, out of midair, onto the floor.

Since Rhea died, I always hoped she'd come back to haunt me something like that. Of course I wanted for her spirit to be at peace and for her body to finally experience the healing it didn't find in life, but I also longed for some sign that she was okay. Over the years, various people have reported that they've dreamed about her and that in these visions she smiles mysteriously and tells them she is all right. But I never saw or heard anything myself, so I did the best I could to lay her ghost to rest. I wrote letters-never-sent to her and was relieved to find that they didn't contain any revelations that she hadn't already known when she died. Often, in grad school, I would drive out at night to Sherwood Memorial Gardens and lie in the dark grass by her grave (D was horrified to learn this), listening to the airplanes flying over and the breeze sighing through the grass towards the distant Smokies. Sometimes, if the flight pattern lined up and I listened closely, a jet would come in for its final approach, and just afterwards, I would hear the faint sound of a second, ghost jet floating through the air above me. While the field surrounding her plot is lush and green, grass has never grown on top of her grave. That rectangle of ground always stayed muddy and dirty, as though it had just been filled in.

During the daylight hours, I would see dragonflies and think of the Waterbug Story that gave my family comfort after she died. Maybe she was nearby but unrecognizable. In a kind of shorthand, my parents and I took to saying things like, "I saw Rhea today, hovering in front of my windshield at a traffic light. She was gold this time."

I guess it makes sense that we would want to believe our beloved girl came back as a glittery, hovering creature. When my mom asked Nana a few months ago what form she'd choose, she said to look for a monarch butterfly after she was gone. We like creatures, in my family. There's also the fact that, at my parents' house, we've got ourselves quite a pet cemetery. At last count, there are at least fifteen cats buried out back in the woods. Even though they're only cats, my mom takes the possibility of their haunting her fairly seriously. When Bear was terminally ill, Mom said the same thing she did when my grandmother was close to death: "Some animals want your help when they're close to death. Hog wanted me to speed things up by putting him to sleep when he could no longer enjoy being fed and petted. Bear on the other hand would have haunted me if I'd done anything to make things go faster. So would Grandmother. They were stubborn. They wanted to do it themselves. You just have to know the animal well enough to know what will (or won't) give her peace when she goes."

|

| Wiki entry for "revenant." (See also "ghost.") |

Some literary examples? In Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff, in agony over Catherine's death, pleads with her corpse:

"Where is she? Not THERE—not in heaven—not perished—where? Oh! You said you cared nothing for my sufferings! And I pray one prayer—I repeat it till my tongue stiffens—Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest as long as I am living; you said I killed you; haunt me, then! The murdered do haunt their murderers, I believe. I know that ghosts have wandered on earth. Be with me always—take any form—drive me mad! only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you!"Similarly, when a strange young woman named Beloved shows up in Toni Morrison's eponymous novel, the character Sethe comes to believe it is the ghost of the daughter she murdered. Tormented by guilt, Sethe is slowly eaten alive by Beloved's appetites and tantrums. Or consider the final Harry Potter book, where we learn after the fact that even the wise Albus Dumbledore was infected with a mortal curse when, seduced by the promise of conjuring his sister's and mother's ghosts and being able to apologize to them for his youthful mistakes, he put on the Resurrection Stone ring. Like the Peverell brother driven mad by the reluctant, insubstantial ghost of his dead love, he learns too late that his loved ones cannot return because they no longer belong to the world of the living. Alice Sebold's novel The Lovely Bones gives us Susie Salmon's story from the girl's own point of view: murdered by her serial killer neighbor, she tries to help her family discover the crime and thus move out of purgatory into the real afterlife.

From the other side of things, in Death Tractates, Brenda Hillman complains that she tries to accept the loss of her friend and mentor, "But things kept coming through the panel of death: / doves took off / outside the window: click click click." In another, even more haunting depiction of souls returning as animals, Jack Gilbert imagines that his late wife has been reincarnated unexpectedly as a neighbor's dog:

The strange truth is that sometimes a paranormal experience can be catalyzed by the most prosaic, pragmatic occurrence, whether it's meeting a new dog or sitting out a spell of summer storms.

For instance, take what happened in 1816, also known as The Year without a Summer (when I was telling D recently what I'd read about it, I only got as far as the first four words of that phrase and the initial letter of the fifth before he finished, "...without a Santa Claus...?"). It's also colloquially known as The Summer that Never Was, or my favorite: Eighteen Hundred and Froze-to-Death. After the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, a volcanic winter occurred for the next year and a half. Ash from the volcano spread around the earth's atmosphere, causing greater reflectivity of sunlight and sending the Northern Hemisphere's weather into a tizzy. According to the Farmer's Almanac, a high temperature of 46 degrees was recorded in Savannah on the Fourth of July the next summer. In Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, the authors report, "In the terrible winter of 1817 [...] the thermometer plummeted to twenty-six below zero and Buttermilk Channel iced over so thickly that horse-drawn sleighs crossed to Governors Island" (494). In fact, even in June, snow fell in several northeastern states, and lakes froze over as far south as Pennsylvania.

Across the pond, 1816 also had cultural effects. The preternaturally vivid sunsets in the paintings of J.M.W. Turner (my favorite), it has been argued, were due largely to the veil of sulfuric acid aerosol that cloaked the atmosphere, distorting and coloring the sun's rays. The year was significant in literary terms, as well. It was the year that Percy Shelley's estranged first wife Harriet committed suicide, and the year that he spent a summer vacation in Switzerland with a couple of friends and his soon-to-be wife Mary (née Wollstonecraft), whose own half-sister Fanny would also kill herself later that year. Because of the nasty weather, the vacationers were marooned inside the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva. Perhaps inspired by the inexplicable tumult outside, they entertained themselves reading French and German horror stories, until Lord Byron, one of the quartet, suggested a contest: whoever could write the scariest supernatural tale would win. From this contest sprang the literary beginnings of two of our most horrifying supernatural beings: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and John Polidori's The Vampyr (based on Lord Byron's "The Burial: A Fragment"). In her own words, Shelley writes:

|

| Source: here |

We talk of Ghosts. Neither Lord Byron nor M. G. L. ["Monk" Lewis] seem to believe in them; and they both agree, in the very face of reason, that none could believe in ghosts without believing in God. I do not think that all the persons who profess to discredit these visitations, really discredit them; or, if they do in the daylight, are not admonished by the approach of loneliness and midnight, to think more respectfully of the world of shadows. (71-2)

Percy has a point. It is a whole lot easier to scoff at the world of the supernatural when it's light outside and you're with other people.

There are ghosts in my own past, in my family's past, that I can't yet exorcise. They drift around family gatherings, around my dreams, around items in the house.

|

| This man sure could tell a story. |

It is hard... for me to project myself backward to those days when... none of these innovations were known, none of these were available... and certainly, from your point of reference, I can understand your difficulty... but I hope to preserve... or to communicate to you... what life was like in the simpler days. It must be difficult to understand how it would be to, for instance, spend an evening... when you don't have a television to watch or even a radio to listen to, when you don't have electricity to even read by... In the early days of the kerosene lamp and the fireplace, we didn't spend great evenings reading, entertaining ourselves through external means. They were almost entirely internal: through playing games, through sitting around the fire playing a game of checkers or a game of Fox and Geese (Fox and Geese, incidentally, is a board-type game we played with grains of corn.) Generally speaking, we didn't have... didn't require... I guess, didn't expect... a lot of entertainment as such. When night came, and we had finished eating, we sat and talked—and that is an unusual thing in today's world.... From this came many of the verbal traditions in my life... in Lucille's life... almost all of the older folks told the usual—we called them "haint tales" (or haunts, ghost stories)... the stories of the wild animals— particularly the panthers—"painters," we called them. They told these stories and scared the daylights out of you, and then told you to go to bed.

|

| Eli and Arie, November 1960 |

But even these hard mountain folks weren't always as unrelentingly rational about the supernatural as I give them credit for. My Pawpaw's father Eli was so famously spookable that once, just for meanness, while she was ironing in the kitchen, his wife Arie pitched a small fire log out into the woods behind the outhouse, just as Eli was emerging from his evening visit to the privy. The pop of the log into the dead leaves startled their old tom cat, who happened to be nearby and who leaped, claws unsheathed, onto his owner's nightshirt-clad back. Eli struck out in a dead sprint towards the house, along with the cat, who had hit the ground running, too. They both arrived at the back step simultaneously, with the cat underfoot nearly tripping Eli, who exploded at him, "Get out of the way, you son-of-a-bitch, and let somebody run who can!" Arie howled with laughter, as she did every time she told that tale over the years. Pawpaw recalls, "Papa eventually trained himself to 'go' in the morning instead of at night, I think more out of fear than anything else." (As for Arie, my uncle swears that one misty morning years after she died, in the upper orchard above her house he locked eyes with a wild turkey that had her very gaze.)

From my great-grandfather Eli, I inherited a similar jumpiness. Pawpaw used to play a game called Jim the Dog with me and my cousin Chris when we were very little. It was deeply unsettling to discover that the same man who called me "little hon" and used his pocket knife to gently and laboriously carve tiny, doll-sized baskets for me out of acorns was at other times possessed by the spirit of a demon dog. Much like Laura Ingalls' beloved Pa:

And indeed, there were also scary stories I heard in my childhood that were real. For instance, I think of another frightening one from Little House in the Big Woods, which describes the small cabin in Minnesota where Ingalls grew up. There, her father told her a "painter tale" about her own ancestor:

The message was clear: don't go into the woods alone and unarmed. There are creatures who mean you harm.

But what if those creatures live in the house with you? What if they're not literal? All that darkness, and walls that hold it in instead of keeping it out. There are ghostly figures that people my past. Another great-grandfather, a charismatic schoolteacher-poet, lay down early one morning on the chaise on his front porch, pointed a shotgun at himself, and pulled the trigger with his big toe. A couple of years later, two of his boys died from carbon monoxide poisoning when they were trapped one night inside their truck in a West Virginia snowbank. Still another great-grandfather, a jeweler, drank a glass of jewelry cleaner sitting on the mantle, having allegedly mistaken it for water, some months after he had lost his wife to cholera. Some of my ancestors were not happy. They screamed. Their spirits moaned. They were haunted by things.

Recently I read a book lent to me by my analyst: The Tales of Moominvalley, by Tove Janssen. "I wish someone had read these to me when I was a little girl," she said. "They are such wonderfully grounded characters."

They are. I found several of them so relatable that they made me squirm a bit (ahem, the Fillyjonk). Others felt unbelievably similar to a couple of people I love dearly. In particular, I loved "A Tale of Horror," the story of the Whomper, a young teller of tall tales who panics his mother when he informs her blithely that his baby brother has been eaten by mud-snakes. (His brother is happily eating dirt in the yard.) Later, he frightens himself when he imagines a Ghost Wagon: "Suddenly he felt cold and afraid, from his stomach upward. A moment ago the Ghost Wagon hadn't existed. Nobody had ever heard of it. Then he thought it up, and there it was. [...] Somewhere in the distance the Ghost Wagon started rolling, it whisked red sparks over the heather, it creaked and cracked and gathered speed." The Whomper is completely convinced of everything he says because his imaginings are his reality. This reminded me a little of my own figmental exploits with my siblings.

When we were in elementary school, Rhea and Jeff and I used to travel to Spooky Island at least once a week. The journey involved dragging one of the ladder-backed chairs from the kitchen table into my parents' walk-in closet, turning it up on its side like a sled with its legs pointing forward, and sitting in a line on the slats, each of us between the knees of the one behind us, like luge riders. In almost every case, we traveled to the island to rescue someone who had been kidnapped by our imaginary nemesis Kevin. Sometimes it was Bobba, Kevin's invisible infant sister, whom he would frequently abduct in order to lure us to his dangerous hideout. The journey was treacherous. The waters that lay between us and Spooky Island were populated by all kinds of creatures, both real and supernatural: sharks, electric eels, ghosts, electrified ghosts that could electrocute us if we even stepped foot off our "boat" onto the carpet "sea." We very nearly died every time we went there. It became a ritual. One of us would announce on a sunny afternoon when we'd gotten home from school, "We need to go to Spooky Island today." Jeff would always be captain. Rhea and I were usually busy fending off the ghosts and predators that tried to climb aboard. Sometimes, one of us would get life-threateningly electrocuted or possessed and have to be rushed to the imaginary Greenwood Hospital. It was never enough to kill us—just enough to frighten.

Years later, when Rhea's friends and family made squares for a quilt that she would take with her to Nashville for her transplant, the first image I thought of for my contribution was the one you see below. It makes sense to me now that my instinct was to send her into the hardest trial of her life with a reminder of our always-victorious battles against invisible malevolent forces—my square, one piece of a blanket that could protect her and keep her warm.

Her house had a very distinctive smell of stale cigarettes and cherry air freshener (nice, I know) and I started smelling it in my house. I didn't smell it everywhere, but it was like I would walk through it in spots just at weird random times and it was usually in my bedroom when I would come in after [my ex-husband] was already asleep. I kinda started to feel like she was in there with him... Then one night I was going to bed, it was dark and he was already asleep and it was like I walked through a spirit at the foot of my bed. It was like a rush went through me and then was gone, almost like going over a hill in a car really fast. So weird! But I don't smell the smells anymore, so it's like she's gone now. So strange.When I wrote her back, I told Lauren I believed her. I said that until recently I'd always thought that heaven or the afterlife was "up there" in another place and we were "down here," but that after Rhea's death and years of thinking about the issue, I had decided that if there is an afterlife, it's more "over there" than "up there." Maybe it's another, as-yet undiscovered dimension, and perhaps we just aren't evolved enough beings yet to be able to perceive it. By that line of thought, our late friends and relatives could be quite close by (Brenda Hillman says this), yet still inaccessible to us.

I don't know why I've ended up writing you a research paper on ghost references and put off telling you my own story. Well, actually, I do know why. I feel more than a little defensive about it. I accept the veracity of other people's paranormal experiences, but I don't know if you'll do that for me. I'm worried that I'm going to sound like the Whomper, telling tall tales. Or I'm worried that you'll try and debunk my story. But the truth is, it shouldn't matter. This is what I heard and saw. Four years ago, this happened to me:

On Saturday night late, D and I were sitting in the living room at my parents' house, and we had been having this fairly serious conversation about Rhea, my grandmother (who had suddenly seemed really vacant and sick when I visited her at the nursing home that afternoon, and I had wondered aloud if it was the last time I would see her alive), and our pets. D was asking me whether, when his two cats died, he could bury them in our backyard with the other animals in my family's "pet cemetery." I have no idea how many animals are actually buried back there now, but it's a lot.

It was very quiet in the house, and then Jane, my mom's black cat, woke up from her nap on the couch and went to the kitchen. A few seconds later, D said, "Did you hear that? It sounds like footsteps." He said it wasn't the cat; they were definitely heavy, human footsteps, like when my mom comes down to get a snack in the middle of the night - but no one had come downstairs. (We asked my parents the next day, and they said definitely that neither of them had gotten out of bed then.)

A few seconds later, the two old clocks in the room started to chime midnight, and we both looked at each other, because we heard this weird music that sounded kind of like instrumental soundtrack music. He said, "Do you hear that, too?" and we both just sat there for a minute, listening. We couldn't tell where the music was coming from; it was kind of faint and muffled. When the clocks stopped chiming, the music stopped, too. We sat forever and talked through everything we could think of that could have made the noise, but it seemed clear that it wasn’t any of those things. I asked my parents the next day about it, and they thought about it but had no idea what could have been playing the music, either.

Geeze, this is a long story! Anyway, after we heard the noises, I was telling D that in all the years since Rhea died, I had never really felt any "presence" in the house, not like you would expect if she were haunting it. Then he told me that just before he heard the footsteps and the clocks striking and the music, he had felt convinced that Rhea was there, like he expected her to walk in any minute and sit down with us. He asked me if there was any significance to the date, and I didn't know, so we went and found Rhea's journal from when she was sick, and looked up August 9. It turned out that it was the first entry in the journal, and it was the day she had sat down with Mom and planned her funeral. The entry was very sad and upsetting. She said that she was angry at God - she put it, "it's like he's a friend that I'm mad at" - and she wrote that she was angry because she was 19 and had to plan her own funeral and because she would never have children. She said she felt someone owed her an apology.

D and I were both a little freaked out by it. Despite all the years of people telling me that Rhea has appeared to them in dreams and indicated that we aren't to worry about her because she's happy where she is, I had never actually had an experience like that myself. D and I agreed that we've always been a little skeptical about ghost stories - we both always thought it was certainly possible that ghosts or spirits were nearby and could be perceived by people, but neither of us had ever personally seen any evidence of it. The thing is, it wasn't scary, like with an angry person or presence - the music was actually a comforting melody - but it was very, very eerie.

What does this mean? I don't know. I can tell you that that day was the last time I saw my grandmother alive. And a little over a year later, the cat Jane Black died, too, and took her place in our feline graveyard.

Likewise, I can neither confirm nor dispel your beliefs (or skepticism) about ghosts. I won't pretend to. All I can relay to you is what I've seen, heard, and read.

Almost every morning when I sit down in front of the computer with my coffee, my Nana shows up in my Facebook chat lineup. There's a rational explanation for this, of course. Her computer and login information are still in the possession of my family, who haven't yet notified Facebook of her passing. So there she is, most days, smiling out of that tiny profile picture with her beloved Al. The little dot beside her name glows green with readiness, and I can almost convince myself she's about to instant message me from the Other Side.

In the end, who is to say she isn't?

__________________________

In honor of this week's deathly holidays, here is a slightly macabre recipe. The great thing is that it can be made with whatever you have on hand, including leftovers. Don't forget the white barbecue sauce, an Alabama specialty.

I made it up one Saturday morning recently after D suggested deviled eggs for breakfast. I scoffed a little at first, but then I came around to seeing things his way. I threw the rest of this together, served it up in a bowl, and D took a bite and declared, "We will call this Breakfast with the Devil."

breakfast with the devil

for two, of course

4 eggs

1 tbsp. mayonnaise

1 tsp. Dijon mustard

1 tsp. white vinegar

1 tbsp. pickle relish (I finely chopped up 1/4 of a baby kosher dill pickle)

cheesy grits (I recommend these)

leftover pulled pork or ham

white barbecue sauce (Miss Myra's, if you're in Birmingham and can get it)

regular barbecue sauce (optional)

chopped chives

kosher sea salt and black pepper

Make your deviled eggs. Hard-boil a bunch of eggs. Peel them carefully. Cut them in half, reserving the yolks in a large bowl, and putting the white halves on a plate. With a fork, mash the yolks well. Add mayo, mustard, vinegar, pickles, and salt and pepper to taste. Use a whisk, if you like, to get the mixture really smooth. Spoon it into the cups of the whites.

Fix your grits. Any kind are great, including the packaged flavored kind. I used a combination of cheddar-flavored and bacon-flavored instant grits, and I added some chopped bacon to it, too.

Put a half the grits into a large bowl. Scatter some reheated pulled pork or ham around the bowl. Nestle the deviled egg halves on top. Drizzle some barbecue sauce(s) over everything. Sprinkle chives here and there, and serve.

Prepare for a long nap. If you eat this often, prepare for a dirt nap.

In the end, who is to say she isn't?

__________________________

In honor of this week's deathly holidays, here is a slightly macabre recipe. The great thing is that it can be made with whatever you have on hand, including leftovers. Don't forget the white barbecue sauce, an Alabama specialty.

I made it up one Saturday morning recently after D suggested deviled eggs for breakfast. I scoffed a little at first, but then I came around to seeing things his way. I threw the rest of this together, served it up in a bowl, and D took a bite and declared, "We will call this Breakfast with the Devil."

breakfast with the devil

for two, of course

4 eggs

1 tbsp. mayonnaise

1 tsp. Dijon mustard

1 tsp. white vinegar

1 tbsp. pickle relish (I finely chopped up 1/4 of a baby kosher dill pickle)

cheesy grits (I recommend these)

leftover pulled pork or ham

white barbecue sauce (Miss Myra's, if you're in Birmingham and can get it)

regular barbecue sauce (optional)

chopped chives

kosher sea salt and black pepper

Make your deviled eggs. Hard-boil a bunch of eggs. Peel them carefully. Cut them in half, reserving the yolks in a large bowl, and putting the white halves on a plate. With a fork, mash the yolks well. Add mayo, mustard, vinegar, pickles, and salt and pepper to taste. Use a whisk, if you like, to get the mixture really smooth. Spoon it into the cups of the whites.

Fix your grits. Any kind are great, including the packaged flavored kind. I used a combination of cheddar-flavored and bacon-flavored instant grits, and I added some chopped bacon to it, too.

Put a half the grits into a large bowl. Scatter some reheated pulled pork or ham around the bowl. Nestle the deviled egg halves on top. Drizzle some barbecue sauce(s) over everything. Sprinkle chives here and there, and serve.

Prepare for a long nap. If you eat this often, prepare for a dirt nap.

No comments:

Post a Comment